I am naturally shy, so even now, several years after publication, it still surprises me that my book, It’s Not What You Say, It’s The Way You Say It!, is all about emotion. It’s about the way you come across, not the comfortable rationale of what you say.

Starting out armed with the experience of over 1000 pitches –many successful, some not but learning from both – I intended to write mainly for the business reader, quoting case histories together with lessons for success. This format has however been done well by others and I was determined to be if not better, then different.

My talented editor pointed out that the pitching principles in my first outline were the same for all live persuasive communication, principles for the most part formulated by the ancient teachers of rhetoric over two thousand years ago. It made complete sense to broaden potential readers to all who present or speak, interview or audition, preach or propose. This in turn determined a communication approach in the book that was easy and accessible to all readers, an approach that was itself a demonstration of the way to come across with impact, bringing ideas alive with wit and visual imagination.

While the principles are indeed common, there is also in my view one basic error which lies at the heart of many unsuccessful pitches or interviews. It is an error based on the very human concern to keep on trying to improve the content – the script, the PowerPoint, the argument – right up until the last possible moment.

Much midnight oil is burnt striving to perfect or find a competitive edge. And all of this reasonable, or rational, use of resource, effort and energy restricts, sometimes to zero, time spent on injecting the emotional energy essential to performance.

We forget that people act on emotion, then justify with reason.

We ignore what our experience tells us, as did Dale Carnegie ‘When dealing with people, let us remember we are not dealing with creatures of logic. We are dealing with creatures of emotion, creatures bristling with prejudices and motivated by pride and vanity.’ Or as Maya Angelou so beautifully said ‘I’ve learnt that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.’

With words like these inspiring me, it will be no surprise that my central premise, developed through the book, is that emotion is at the heart of any successful pitch.

To bring this central thought alive in a compelling way, some 50 ideas are explored using clever illustration and creative headlines, aiming to stimulate and educate in a memorable way. Through the book, getting to the emotional heart is considered in three ways. What is the emotional response you seek? How do you resist content pressure to give priority and space for emotion? How can you bring the right levels of emotion to your performance?

The importance of getting under the skin of your audience is covered as is the essential skill of listening, really listening, something often overlooked in the excitement of a pitch. Without this, the emotional responses sought will be easily missed but there will in all situations be two responses that are paramount.

They were very well articulated in a perceptive and revealing article some years ago in a marketing journal in the UK. The writer was head of a company, AAR, which specialised in guiding clients through the agency selection process. He had gained unique insight from observing his clients firstly receiving the pitches, over 600 of them, and then discussing their decisions.

Surprise, surprise, his conclusions were that it was not the brilliance of the proposed strategy or creative solution that carried the day. More often than not the decision came down to their assessment of two simple questions they asked themselves, the first being:

‘Will I like these people?’ (as partners/suppliers/staff ) with an allied ‘Do they (the pitch team) like each other?

Both are loaded emotionally. Of course, most people pitching will pass the likeability test in their normal lives but are they as likeable under the tension of the competitive arena? They may be worrying about their words, their visual aids, often subject to last minute changes (the curse of PowerPoint), the hand-overs. A team that may be the best of friends can, under pressure, easily give off vibes that signal otherwise. If they do, the decision will go against them. Rehearsal is discussed later but worth noting that in my experience ‘rehearsal makes nice people nicer.’

The second question the decision takers ask themselves is this, “How much do these people really want my business? How hungry are they?

Hunger is not to be mistaken for desperation. Nor is it the same as the polished professional enthusiasm you expect in any pitch. Hunger is not something you proclaim. You ooze it by being hell-bent on doing more, asking more, leaving no proverbial stone un-turned.

Judging the emotional response is as critical in the one-on-one interview as it is on a global stage. Ten years ago London won the bid to host the 2012 Olympics. Five cities were competing in the final live pitch to the International Olympic Committee with Paris, in rational terms of delivering a successful event, the clear favourites. London’s hopes rested on persuading the IOC to act on emotion.

They did this through a highly emotional appeal expressed as “London’s vision is to reach young people all around the world, to connect them with the inspirational power of the Games, so that they are inspired to choose sport”.

They knew if they failed to connect, they would fail

Many months after London won the bid, Lord Coe was asked if there was one thing that he felt was at the heart of their success. His reply: “It was all down to the emotional connection.”

A study of this bid, widely discussed as a case history demonstrating the perfect pitch, shows that a relentless attention to detail and massive resource were committed to the essential Technical submission – the ‘rational’ phase. During this however the London team never lost sight of the emotional end game. They built ‘emotional priority’ into their preparation and went into the final live pitch knowing the emotional levers to use. Or, in other words, they understood how to arrange and emphasise the key messages that would best resonate and persuade.

The concept of ‘arrangement’ is not new. It is one of the Five Cannons of Rhetoric defined by the ancient writers such as Aristotle, Cicero and Quintilian who said: “The whole art of oratory, as the most and greatest writers have taught, consist of five parts: invention, arrangement, style, memory and delivery.”

Often overlooked, it is the clever arrangement of your argument that enables you to express it to greatest effect. The Greek word was taxis– to arrange your troops for battle. A nice thought! To win the (pitch) battle you need to lead with your key attacking force- your proposition or promise, (see Coe’s vision).

Don’t bury it somewhere in the depths of the charts. Describe this central thought in words that lend themselves to passionate articulation, not like so many dry corporate mission statements.

I suggest in my book you think of them as “words to woo your lover…”You should be able to condense your story or presentation to 50 persuasive words that capture the hearts, not just the minds of your audience. Some elevator pitches miss out on the emotional component. Shakespeare, of course, said it best “Thou cannot speak of that thou dost not feel”

Then, pursuing the concept of arrangement, my suggestion is to obey the ‘rule of three’ (omnium trium perfectum). Or, put another way, don’t make the mistake of presenting a whole ‘shopping list ’of facts and arguments. Lists have their place on a fridge door, as a reminder of what to do or buy. Lists do not have a place when you want to communicate with your audience. They deny emotional expression. You may have 20 burning issues to get across, but the audience will not easily take them in, or be moved by them, if you do not have a simple structure that guides their listening.

To make life easier for them you need to arrange your arguments (your troops) into no more than three themes that support your promise or subject. So, ‘burning issues’ can be arranged into ‘hot’, red hot’ and ‘flaming.’ Each of these can be separately developed but with no more than three supporting points.

Finally, having identified the emotional response you want and then arranging your messages to allow emotion in, what can be done to perform with emotion on the day? Rising to the occasion and outperforming your rivals, rather than the great solution, will so often be the difference between getting the job or the assignment, or not.

This is the essential role of rehearsal. In my view it is the most neglected and ignored ingredient of pitch preparation yet is your best return on investment.

Delivering a pitch, whether from a platform or across a boardroom table or over coffee at Starbucks, you are on stage.

You need to tap into the actor in you. Connecting emotionally with a large group or a single interviewer in conversation, calls for a performance that reaches out, bringing emotional resonance to the words. Actors start off fully confident in their brilliant scripts written by a William Shakespeare or a Tennessee Williams. They are not worried about their content. All they are concerned with is how they can make their script come alive to their audience. No matter how experienced they may be, they rely on rehearsal to gauge their performance and its impact.

They don’t do this alone, practising to a mirror. That can be a useful exercise for checking timing or your memory, but it is not rehearsal. Rehearsal requires that you have someone standing in as an audience, like a director, who can tell you how you come cross. You can’t judge yourself!

My advice to any presenter is to find a trusted colleague to rehearse you, and, where possible, rehearse each pitch or speech before you deliver it. Ask them not to comment on the words but on your performance, on the way you said it and on how it makes them feel and think.

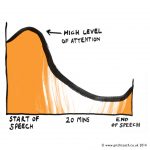

Was my energy level high? Was it clear? Was my passion evident? (Words with huge meaning can be ‘lost’ in translation if spoken poorly. In any pitch you need the balance of logos (appealing to reason) and pathos (appealing to the emotion).Was I making eye contact? If you are looking down constantly, reading from notes, you lose connection and lose your audience. In rehearsal you can identify this and other mistakes and correct them. Was my body language open and expressive? Was I confident? Was I likeable? And, finally, was I myself, or better?

As Oscar Wilde reminded us, “Be yourself; everyone else is taken.”

The ‘sin’ of failing to rehearse is wrapped up in my earlier premise that time spent on content, at the expense of performance is the common error. The excuse for not rehearsing is given as lack of time (although in truth it is one of many avoidance mechanisms!)

Too much time is spent being rational, striving to create perfect content. Too little time is spent perfecting delivery, being emotionally on song. If you want to win, let your emotions show and take this advice written two thousand years ago

“I would not hesitate to assert that a mediocre speech supported by all the power of delivery will be more impressive than the best speech unaccompanied by such power.’ Quintilian, Institutes of Oratory

Michael Parker. IT’S NOT WHAT YOU SAY, IT’S THE WAY YOU SAY IT!

This bias can be explained, if not excused, by ‘tradition’. After all the word marriage comes from the Latin word ‘mas’ meaning male or masculine. And ‘tradition’ still influences much of the ceremonial. The Anglo-Saxon father would use his daughter as a form of currency to pay off his debts, the bride standing on the left is rooted in the groom’s need to keep his sword arm free for action to prevent ‘bride kidnapping!’

This bias can be explained, if not excused, by ‘tradition’. After all the word marriage comes from the Latin word ‘mas’ meaning male or masculine. And ‘tradition’ still influences much of the ceremonial. The Anglo-Saxon father would use his daughter as a form of currency to pay off his debts, the bride standing on the left is rooted in the groom’s need to keep his sword arm free for action to prevent ‘bride kidnapping!’ If you are speaking as a bride, best woman or mother you can find these constant principles in my book. (So will the men.)

If you are speaking as a bride, best woman or mother you can find these constant principles in my book. (So will the men.)